Purple Haze all in my brain

Lately things don’t seem the same,

Actin’ funny, but I don’t know why

‘Scuse me while I kiss the sky

You

could interpret this as using LSD (all in my brain), which has an

effect on the mind and behaviour (actin’ funny) of the abuser. Although

Hendrix wasn’t the only musician to have the psychedelic drugs buried

within his songs. Jefferson’s Airplane song ‘White Rabbit’ written in

1967 could also be seen in a similar way.

When logic and proportion

Have fallen sloppy dead

And the white knight is talking backwards

And the Red Queen’s off with her head,

Remember what the dormouse said:

“Feed your head, feed your head”

The

last two lines of the song could be seen as what the use of these drugs

meant to the counterculture and Timothy Leary; using them for a greater

mind expansion. Not only were the counterculture bands influencing the

American youths radical behaviour with their lyrics, the persona of many

of the musicians and their lifestyle promoted what seemed to sum up the

counterculture’s attitude.

Jim Morrison was the lead singer of The Doors whose name came from a book popular among the counterculture Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley. Morrison is regarded as one of the most iconic, charismatic and pioneering front men in rock music history. Known for his alcohol and drug abuse and numerous run-ins with the law, the singer and his band had a huge impact in the radicalisation of American youth. As drummer John Densmore stated in 2002: ‘I think we were a target because by then we really represented the anti-war movement and the kids versus the establishment’.

Many of the Doors songs have been linked to psychedelic drugs (Crystal Ship, 1967 and Light My Fire, 1966). When the Doors played a sold-out concert at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968, there were copious accusations that Morrison wasn’t on form at the concert due to drugs. Three years later he died in Paris, a death related to drugs and alcohol. It was this radical lifestyle, influencing American youths, which led to the deaths of many counterculture musicians including Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

With the counterculture music it appeared drugs and rock could not be separated. As Ringo Starr himself said marijuana ‘made a lot of difference to the type of music and the words’. The counterculture was producing new musical styles and new subject matter for lyrics.

The Beatles song ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ spells out the words LSD, although this is still denied as being deliberate by the remaining band members. Other Beatles songs that are notoriously linked to drugs include ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. The latter, a song suggesting it was written under the influence of LSD and that gives the music its strange psychedelic sound.

To think that the Beatles first conquered America by singing pop songs Love Me Do and Can’t Buy Me Love, with their clean-shaven and distinctive neatly cut hairstyles. When the American youth culture took a turn toward the psychedelic it appears the Beatles followed. Releasing Stg. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band in June of 1967, the same year of the hippie epidemic in San Francisco known as The Summer of Love; the Beatles appearance and sound was more psychedelic than any of their previous releases. Even the front cover of the album is all a little too trippy and psychedelic, similar to the famous album art of the Grateful Dead.

In the lyrics of the Who’s My Generation (1965) they represented the young people versus previous generations:

Jim Morrison was the lead singer of The Doors whose name came from a book popular among the counterculture Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley. Morrison is regarded as one of the most iconic, charismatic and pioneering front men in rock music history. Known for his alcohol and drug abuse and numerous run-ins with the law, the singer and his band had a huge impact in the radicalisation of American youth. As drummer John Densmore stated in 2002: ‘I think we were a target because by then we really represented the anti-war movement and the kids versus the establishment’.

Many of the Doors songs have been linked to psychedelic drugs (Crystal Ship, 1967 and Light My Fire, 1966). When the Doors played a sold-out concert at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968, there were copious accusations that Morrison wasn’t on form at the concert due to drugs. Three years later he died in Paris, a death related to drugs and alcohol. It was this radical lifestyle, influencing American youths, which led to the deaths of many counterculture musicians including Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

With the counterculture music it appeared drugs and rock could not be separated. As Ringo Starr himself said marijuana ‘made a lot of difference to the type of music and the words’. The counterculture was producing new musical styles and new subject matter for lyrics.

The Beatles song ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ spells out the words LSD, although this is still denied as being deliberate by the remaining band members. Other Beatles songs that are notoriously linked to drugs include ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. The latter, a song suggesting it was written under the influence of LSD and that gives the music its strange psychedelic sound.

To think that the Beatles first conquered America by singing pop songs Love Me Do and Can’t Buy Me Love, with their clean-shaven and distinctive neatly cut hairstyles. When the American youth culture took a turn toward the psychedelic it appears the Beatles followed. Releasing Stg. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band in June of 1967, the same year of the hippie epidemic in San Francisco known as The Summer of Love; the Beatles appearance and sound was more psychedelic than any of their previous releases. Even the front cover of the album is all a little too trippy and psychedelic, similar to the famous album art of the Grateful Dead.

In the lyrics of the Who’s My Generation (1965) they represented the young people versus previous generations:

I hope I die before I get old, this is my generation

The band were making reference to Free Speech Movement activist Jack Weinberg’s famous quote ‘don’t trust anyone over thirty.’

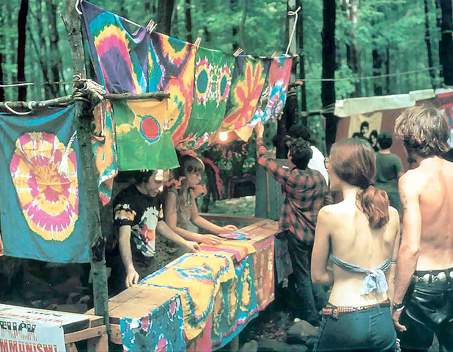

In the later years of the counterculture John Lennon’s vocalising for peace became a huge media factor as he and Yoko Ono took on the crusade for Peace themselves. In 1969 they held a two-week long Bed-In for Peace. Before John Lennon put his name to these radical proceedings, it was Timothy Leary and the young hippies of America who began similar events, the most famous being held in 1967 in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park known as ‘The Human Be-In’.

Here the essence of the counterculture was captured; the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane performed, LSD was sold, and Timothy Leary uttered his famous quote ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out.’ The Human Be-In of 1967 was less about protesting a War and more about celebrating, it was the prelude to the 1967 Summer of Love that made San Francisco the epicentre for the counterculture.

Originally published at atlantismusic.wordpress.com on December 16, 2015.

In the later years of the counterculture John Lennon’s vocalising for peace became a huge media factor as he and Yoko Ono took on the crusade for Peace themselves. In 1969 they held a two-week long Bed-In for Peace. Before John Lennon put his name to these radical proceedings, it was Timothy Leary and the young hippies of America who began similar events, the most famous being held in 1967 in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park known as ‘The Human Be-In’.

Here the essence of the counterculture was captured; the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane performed, LSD was sold, and Timothy Leary uttered his famous quote ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out.’ The Human Be-In of 1967 was less about protesting a War and more about celebrating, it was the prelude to the 1967 Summer of Love that made San Francisco the epicentre for the counterculture.

Originally published at atlantismusic.wordpress.com on December 16, 2015.